THE DOG

Antipathy displayed by Orientals towards the Dog, and manifested throughout the Scriptures—Contrast between European and Oriental Dogs—Habits of the Dogs of Palestine—The City Dogs and their singular organization—The herdsman's Dog—Various passages of Scripture—Dogs and the crumbs—their numbers—Signor Pierotti's experience of the Dogs—Possibility of their perfect domestication—The peculiar humiliation of Lazarus—Voracity of the Wild Dogs—The fate of Ahab and Jezebel—Anecdote of a volunteer Watch-dog—Innate affection of the Dog towards mankind—Peculiar local Instinct of the Oriental Dog—Albert Smith's account of the Dogs at Constantinople—The Dervish and his Dogs—The Greyhound—Uncertainty of the word.

Scarcely changed by the lapse of centuries, the Oriental of the present day retains most of the peculiarities which distinguished him throughout the long series of years during which the books of sacred Scripture were given to the world. In many of these characteristics he differs essentially from Europeans of the present day, and exhibits a tone of mind which seems to be not merely owing to education, but to be innate and inherent in the race.

One of these remarkable characteristics is the strange loathing with which he regards the Dog. In all other parts of the world, the Dog is one of the most cherished and valued of animals, but among those people whom we popularly class under the name of Orientals, the Dog is detested and despised. As the sacred books were given to the world through the mediumship of Orientals, we find that this feeling towards the Dog is manifested whenever the animal is mentioned; and whether we turn to the books of the Law, the splendid poetry of the Psalms and the book of Job, the prophetical or the historical portions of the Old Testament, we find the name of the Dog repeatedly mentioned; and in every case in connexion with some repulsive idea. If we turn from the Old to the New Testament, we find the same idea manifested, whether in the Gospels, the Epistles, or the Revelation.

To the mind of the true Oriental the very name of the Dog carries with it an idea of something utterly repugnant to his nature, and he does not particularly like even the thought of the animal coming across his mind. And this is the more extraordinary, because at the commencement and termination of their history the Dog was esteemed by their masters. The Egyptians, under whose rule they grew to be a nation, knew the value of the Dog, and showed their appreciation in the many works of art which have survived to our time. Then the Romans, under whose iron grasp the last vestiges of nationality crumbled away, honoured and respected the Dog, made it their companion, and introduced its portrait into their houses. But, true to their early traditions, the Jews of the East have ever held the Dog in the same abhorrence as is manifested by their present masters, the followers of Mahommed.

Owing to the prevalence of this feeling, the Dogs of Oriental towns are so unlike their more fortunate European relatives, that they can hardly be recognised as belonging to the same species. In those lands the traveller finds that there is none of the wonderful variety which so distinguishes the Dog of Europe. There he will never see the bluff, sturdy, surly, faithful mastiff, the slight gazelle-like greyhound, the sharp, intelligent terrier, the silent, courageous bulldog, the deep-voiced, tawny bloodhound, the noble Newfoundland, the clever, vivacious poodle, or the gentle, silken-haired spaniel.

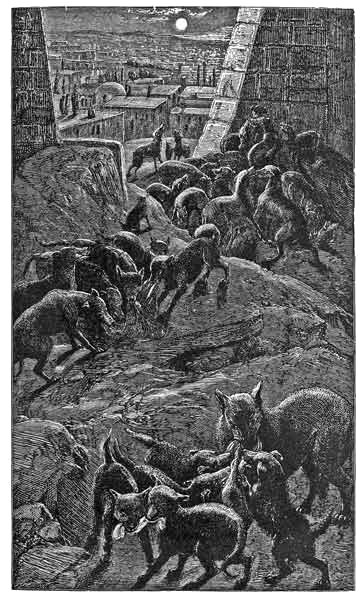

As he traverses the streets, he finds that all the dogs are alike, and that all are gaunt, hungry, half starved, savage, and cowardly, more like wolves than dogs, and quite as ready as wolves to attack when they fancy they can do so with safety. They prowl about the streets in great numbers, living, as they best can, on any scraps of food that they may happen to find. They have no particular masters, and no particular homes. Charitable persons will sometimes feed them, but will never make companions of them, feeling that the very contact of a dog would be a pollution. They are certainly useful animals, because they act as scavengers, and will eat almost any animal substance that comes in their way.

The strangest part of their character is the organization which prevails among them. By some extraordinary means they divide the town into districts, and not one dog ever ventures out of that particular district to which it is attached. The boundaries, although invisible, are as effectual as the loftiest walls, and not even the daintiest morsel will tempt a dog to pass the mysterious line which forms the boundary of his district. Generally, these bands of dogs are so savage that any one who is obliged to walk in a district where the dogs do not know him is forced to carry a stout stick for his protection. Like their European relatives, they have great dislike towards persons who are dressed after a fashion to which they are unaccustomed, and therefore are sure to harass any one who comes from Europe and wears the costume of his own country. As is customary among animals which unite themselves in troops, each band is under the command of a single leader, whose position is recognised and his authority acknowledged by all the members.

These peculiarities are to be seen almost exclusively in the dogs which run wild about the towns, because there is abundant evidence in the Scriptures that the animal was used in a partially domesticated state, certainly for the protection of their herds, and possibly for the guardianship of their houses. That the Dog was employed for the first of these purposes is shown in Job xxx. 1: "But now they that are younger than I have me in derision, whose fathers I would have disdained to have set with the dogs of my flock." And that the animal was used for the protection of houses is thought by some commentators to be shown by the well-known passage in Is. lvi. 10: "His watchmen are blind: they are all ignorant, they are all dumb dogs, they cannot bark; sleeping, lying down, loving to slumber." Still, it is very probable that in this passage the reference is not made to houses, but to the flocks and herds which these watchmen ought to have guarded.

The rooted dislike and contempt felt by the Israelites towards the Dog is seen in numerous passages. Even in that sentence from Job which has just been quoted, wherein the writer passionately deplores the low condition into which he has fallen, and contrasts it with his former high estate, he complains that he is despised by those whose fathers he held even in less esteem than the dogs which guarded his herds. There are several references to the Dog in the books of Samuel, in all of which the name of the animal is mentioned contemptuously. For example, when David accepted the challenge of Goliath, and went to meet his gigantic enemy without the ordinary protection of mail, and armed only with a sling and his shepherd's staff, Goliath said to him, "Am I a dog, that thou comest to me with staves?" (1 Sam. xvii. 43.) And in the same book, chapter xxiv. 14, David remonstrates with Saul for pursuing so insignificant a person as himself, and said, "After whom is the King of Israel come out? after a dead dog, after a flea."

The same metaphor is recorded in the second book of the same writer. Once it was employed by Mephibosheth, the lame son of Jonathan, when extolling the generosity of David, then King of Israel in the place of his grandfather Saul: "And he bowed himself, and said, 'What is thy servant, that thou shouldest look upon such a dead dog as I am?" (2 Sam. ix. 8.) In the same book, chapter xvi. 9, Abishai applies this contemptuous epithet to Shimei, who was exulting over the troubled monarch with all the insolence of a cowardly nature, "Why should this dead dog curse my lord the king?" Abner also makes use of a similar expression, "Am I a dog's head?" And we may also refer to the familiar passage in 2 Kings viii. 13. Elisha had prophesied to Hazael that he would become king on the death of Ben-hadad, and that he would work terrible mischief in the land. Horrified at these predictions, or at all events pretending to be so, he replied, "But what, is thy servant a dog, that he should do this great thing?"

If we turn from the Old to the New Testament, we find the same contemptuous feeling displayed towards the Dog. It is mentioned as an intolerable aggravation of the sufferings endured by Lazarus the beggar as he lay at the rich man's gate, that the dogs came and licked his sores. In several passages, the word Dog is employed as a metaphor for scoffers, or unclean persons, or sometimes for those who did not belong to the Church, whether Jewish or Christian. In the Sermon on the Mount our Lord himself uses this image, "Give not that which is holy unto dogs" (Matt. vii. 6.) In the same book, chapter xv. 26, Jesus employs the same metaphor when speaking to the Canaanitish woman who had come to ask him to heal her daughter: "It is not meet to take the children's bread and cast it to dogs." And that she understood the meaning of the words is evident from her answer, in which faith and humility are so admirably blended. Both St. Paul and St. John employ the word Dog in the same sense. In his epistle to the Philippians, chapter iii. 2, St. Paul writes, "Beware of dogs, beware of evil workers." And in the Revelation, chapter xxii. 14, these words occur: "Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates to the city; for without are dogs, and sorcerers, and whoremongers, and murderers, and idolaters, and whomsoever loveth and maketh a lie."

That the dogs of ancient times formed themselves into bands just as they do at present is evident from many passages of Scripture, among which may be mentioned those sentences from the Psalms, wherein David is comparing the assaults of his enemies to the attacks of the dogs which infested the city. "Thou hast brought me into the dust of death; for dogs have compassed me, the assembly of the wicked have enclosed me." This passage will be better appreciated when the reader has perused the following extract from a recent work by Signor Pierotti. After giving a general account of the Dogs of Palestine and their customs, he proceeds as follows:—

"In Jerusalem, and in the other towns, the dogs have an organization of their own. They are divided into families and districts, especially in the night time, and no one of them ventures to quit his proper quarter; for if he does, he is immediately attacked by all the denizens of that into which he intrudes, and is driven back, with several bites as a reminder. Therefore, when an European is walking through Jerusalem by night, he is always followed by a number of canine attendants, and greeted at every step with growls and howls. These tokens of dislike, however, are not intended for him, but for his followers, who are availing themselves of his escort to pass unmolested from one quarter to another.

"During the hard winter of 1859, I fed many of the dogs, who frequented the road which I traversed almost every evening, and afterwards, each time that I passed, I received the homage not only of the individuals, but of the whole band to which they belonged, for they accompanied me to the limits of their respective jurisdictions and were ready to follow me to my own house, if I did but give them a sign of encouragement, coming at my beck from any distance. They even recollected the signal in 1861, though it was but little that I had given them."

The account which this experienced writer gives of the animal presents a singular mixture of repulsive and pleasing traits, the latter being attributable to the true nature of the Dog, and the former to the utter neglect with which it is treated. He remarks that the dogs which run wild in the cities of Palestine are ill-favoured, ill-scented, and ill-conditioned beasts, more like jackals or wolves than dogs, and covered with scars, which betoken their quarelsome nature. Yet, the same animals lose their wild, savage disposition, as soon as any human being endeavours to establish that relationship which was evidently intended to exist between man and the dog. How readily even these despised and neglected animals respond to the slightest advance, has been already shown by Sig. Pierotti's experience, and there is no doubt that these tawny, short-haired, wolf-like animals, could be trained as perfectly as their more favoured brethren of the western world.

As in the olden times, so at the present day, the dogs lie about in the streets, dependent for their livelihood upon the offal that is flung into the roads, or upon the chance morsels that may be thrown to them. An allusion to this custom is made in the well-known passage in Matt. xv. The reader will remember the circumstance that a woman of Canaan, and therefore not an Israelite, came to Jesus, and begged him to heal her daughter, who was vexed with a devil. Then, to try her faith, He said, "It is not meet to take the children's bread, and to cast it to dogs." And she said, "Truth, Lord: yet the dogs eat of the crumbs which fall from their master's table." Now, the "crumbs" which are here mentioned are the broken pieces of bread which were used at table, much as bread is sometimes used in eating fish. The form of the "loaves" being flat, and much like that of the oat-cake of this country, adapted them well to the purpose. The same use of broken bread is alluded to in the parable of Lazarus, who desired to be fed with the crumbs that fell from the rich man's table, i.e. to partake of the same food as the dogs which swarmed round him and licked his sores. Thus we see that Lazarus was supposed to have undergone the very worst indignities to which poverty could bring a man, and the contrast between himself and the other personage of the parable receives additional strength.

The "crumbs," however liberally distributed, would not nearly suffice for the subsistence of the canine armies, and their chief support consists of the offal, which is rather too plentifully flung into the streets. The Dogs of Palestine are, indeed, much like hy?nas of certain African towns, and act as scavengers, devouring any animal substance that may fall in their way. If the body of any animal, not excluding their own kind, be found lying in the streets, the dogs will assemble round it, and tear it to pieces, and they have no scruples even in devouring a human body. Of course, owing to the peculiar feeling entertained by the Orientals towards the Dog, no fate can be imagined more repulsive to the feelings of humanity than to be eaten by dogs; and therein lies the terror of the fate which was prophesied of Ahab and Jezebel. Moreover, the blood, even of the lower animals, was held in great sanctity, and it was in those days hardly possible to invoke a more dreadful fate upon any one than that his blood should be lapped by dogs.

We lose much of the real force of the Scriptures, if we do not possess some notion of the manners and customs of Palestine and the neighbouring countries, as well as of the tone of mind prevalent among the inhabitants. In our own country, that any one should be eaten by dogs would be a fate so contrary to usage, that we can hardly conceive its possibility, and such a fate would be out of the ordinary course of events. But, if such a fate should happen to befall any one, we should have no stronger feeling of pity than the natural regret that the dead person was not buried with Christian rites.

But, with the inhabitants of Palestine, such an event was by no means unlikely. It was, and is still, the custom to bury the corpse almost as soon as life has departed, and such would ordinarily have been the case with the dead body of Jezebel. But, through fear of the merciless Jehu, by whose command she had been flung from the window of her own palace, no one dared to remove her mangled body. The dogs, therefore, seized upon their prey; and, even before Jehu had risen from the banquet with which he celebrated his deed, nothing was left of the body but the skull, the feet, and the hands.

In Mr. Tristram's work, the author has recognised the true dog nature, though concealed behind an uninviting form: "Our watch-dog, Beir?t, attached himself instinctively to Wilhelm, though his canine instinct soon taught him to recognise every one of our party of fourteen, and to cling to the tents, whether in motion or at rest, as his home. Poor Beir?t! though the veriest pariah in appearance, thy plebeian form encased as noble a dog-heart as ever beat at the sound of a stealthy step."

The same author records a very remarkable example of the sagacity of the native Dog, and the fidelity with which it will keep guard over the property of its master. "The guard-house provided us, unasked, with an invaluable and vigilant sentry, who was never relieved, nor ever quitted the post of duty. The poor Turkish conscript, like every other soldier in the world, is fond of pets, and in front of the grim turret that served for a guard-house was a collection of old orange-boxes and crates, thickly peopled with a garrison of dogs of low degree, whose attachment to the spot was certainly not purchased by the loaves and fishes which fell to their lot.

"One of the family must indeed have had hard times, for she had a family of no less than five dependent on her exertions, and on the superfluities of the sentries' mess. With a sagacity almost more than canine, the poor gaunt creature had scarcely seen our tents pitched before she came over with all her litter and deposited them in front of our tent. At once she scanned the features of every member of the encampment, and introduced herself to our notice. During the week of our stay, she never quitted her post, or attempted any depredation on our kitchen-tent, which might have led to her banishment. Night and day she proved a faithful and vigilant sentry, permitting no stranger, human or canine, European or Oriental, to approach the tents without permission, but keeping on the most familiar terms with ourselves and our servants.

"On the morning of our departure, no sooner had she seen our camp struck, than she conveyed her puppies back to their old quarters in the orange-box, and no intreaties or bribes could induce her to accompany us. On three subsequent visits to Jerusalem, the same dog acted in a similar way, though no longer embarrassed by family cares, and would on no account permit any strange dog, nor even her companions at the guard-house, to approach within the tent ropes."

After perusing this account of the Dog of Palestine, two points strike the reader. The first is the manner in which the Dog, in spite of all the social disadvantages under which it labours, displays one of the chief characteristics of canine nature, namely, the yearning after human society. The animal in question had already attached herself to the guard-house, where she could meet with some sort of human converse, though the inborn prejudices of the Moslem would prevent the soldiers from inviting her to associate with them, as would certainly have been done by European soldiers. She nestled undisturbed in the orange-box, and, safe under the protection of the guard, brought up her young family in their immediate neighbourhood. But, as soon as Europeans arrived, her instinct told her that they would be closer associates than the Turkish soldiers who were quartered in the guard-house, and accordingly she removed herself and her family to the shelter of their tents.

Herein she carried out the leading principle of a dog's nature. A dog must have a master, or at all events a mistress, and just in proportion as he is free from human control, does he become less dog-like and more wolf-like. In fact, familiar intercourse with mankind is an essential part of a dogs true character, and the animal seems to be so well aware of this fact, that he will always contrive to find a master of some sort, and will endure a life of cruel treatment at the hands of a brutal owner rather than have no master at all.

The second point in this account is the singular local instinct which characterises the Dogs of Palestine and other eastern countries, and which is as much inbred in them as the faculty of marking game in the pointer, the combative nature in the bulldog, the exquisite scent in the bloodhound, and the love of water in the Newfoundland dog. In England, we fancy that the love of locality belongs especially to the cat, and that the Dog cares little for place, and much for man. But, in this case, we find that the local instinct overpowered the yearning for human society. Fond as was this dog of her newly-found friends, and faithful as she was in her self-imposed service, she would not follow them away from the spot where she had been born, and where she had produced her own young.

This curious love for locality has evidently been derived from the traditional custom of successive generations, which has passed from the realm of reason into that of instinct. The reader will remember that Sig. Pierotti mentions an instance where the dogs which he had been accustomed to feed would follow him as far as the limits of their particular district, but would go no farther. The late Albert Smith, in his "Month at Constantinople," gives a similar example of this characteristic. He first describes the general habits of the dogs.

"At evening let them return; and let them make a noise like a dog, and go round about the city. Let them wander up and down for meat, and grudge if they be not satisfied"—Psalm lix. 14, 15.

On the first night of his arrival, he could not sleep, and went to the window to look out in the night. "The noise I heard then I shall never forget. To say that if all the sheep-dogs, in going to Smithfield on a market-day, had been kept on the constant bark, and pitted against the yelping curs upon all the carts in London, they could have given any idea of the canine uproar that now first astonished me, would be to make the feeblest of images. The whole city rang with one vast riot. Down below me, at Tophan?—over-about Stamboul—far away at Scutari—the whole sixty thousand dogs that are said to overrun Constantinople appeared engaged in the most active extermination of each other, without a moment's cessation. The yelping, howling, barking, growling, and snarling, were all merged into one uniform and continuous even sound, as the noise of frogs becomes when heard at a distance. For hours there was no lull. I went to sleep, and woke again, and still, with my windows open, I heard the same tumult going on; nor was it until daybreak that anything like tranquillity was restored.

"Going out in the daytime, it is not difficult to find traces of the fights of the night about the limbs of all the street dogs. There is not one, among their vast number, in the possession of a perfect skin. Some have their ears gnawed away or pulled off; others have their eyes taken out; from the backs and haunches of others perfect steaks of flesh had been torn away; and all bear the scars of desperate combats.

"Wild and desperate as is their nature, these poor animals are susceptible of kindness. If a scrap of bread is thrown to one of them now and then, he does not forget it; for they have, at times, a hard matter to live—not the dogs amongst the shops of Galata or Stamboul, but those whose 'parish' lies in the large burying-grounds and desert places without the city; for each keeps, or rather is kept, to his district, and if he chanced to venture into a strange one, the odds against his return would be very large. One battered old animal, to whom I used occasionally to toss a scrap of food, always followed me from the hotel to the cross street in Pera, where the two soldiers stood on guard, but would never come beyond this point. He knew the fate that awaited him had he done so; and therefore, when I left him, he would lie down in the road, and go to sleep until I came back.

"When a horse or camel dies, and is left about the roads near the city, the bones are soon picked very clean by these dogs, and they will carry the skulls or pelves to great distances. I was told that they will eat their dead fellows—a curious fact, I believe, in canine economy. They are always troublesome, not to say dangerous, at night; and are especially irritated by Europeans, whom they will single out amongst a crowd of Levantines."

In the same work there is a short description of a solitary dervish, who had made his home in the hollow of a large plane-tree, in front of which he sat, surrounded by a small fence of stakes only a foot or so in height. Around him, but not venturing within the fence, were a number of gaunt, half-starved dogs, who prowled about him in hopes of having an occasional morsel of food thrown to them. Solitary as he was, and scanty as must have been the nourishment which he could afford to them, the innate trustfulness of the dog-nature induced them to attach themselves to human society of some sort, though their master was one, and they were many—he was poor, and they were hungry.

Once in the Scriptures the word Greyhound occurs, namely, in Prov. xxx. 29-31: "There be three things which go well, yea, four are comely in going: a lion, which is strongest among beasts, and turneth not away for any; a greyhound; an he-goat also; and a king, against whom there is no rising up." But the word "Greyhound" is only employed conjecturally, inasmuch as the signification of the Hebrew word Zarzir-mathn?im is "one girt about the loins." Some commentators have thought that the horse might be signified by this word, and that the girding about the loins referred to the trappings with which all Easterns love to decorate their steeds. Probably, however, the word in question refers neither to a horse nor a dog, but to a human athlete, or wrestler, stripped, and girt about the loins ready for the contest.

Более 800 000 книг и аудиокниг! 📚

Получи 2 месяца Литрес Подписки в подарок и наслаждайся неограниченным чтением

ПОЛУЧИТЬ ПОДАРОКДанный текст является ознакомительным фрагментом.